Latin Quarter - Pantheon

Built to symbolise religion and power

Portrait of Louis XV, by M. Quentin de La Tour

The first church built by Clovis and designed to house the remains of Saint Genevieve established in a stroke an emblematic connection between religion and monarchic power. The new church of Saint Genevieve, now known as the Pantheon, owes its origins to a pious vow made by Louis XV in 1744.

Since its inception, this place has been solemnity itself. From the moment when the first stone was laid in 1764, the site became a theatre of spectacular ceremony. An immense trompe l’oeil painting displayed a perfect representation of the future monument, the plans for which Louis XV had received from the architect Jacques-Germain Soufflot. The latter died in 1780, ten years before the monument was complete, so he never saw the final result of his work, which was not completed until 1790.

The entry of the first Great Men

Voltaire dans son cabinet de travail

The beginning of the Revolution changed the vocation of the monument. A decree issued by the constituent Assemblee on 4 April 1791 transformed the new church of Saint Genevieve into the Pantheon in order that “this temple of religion should become a temple of nation, that the tomb of a great man should become the altar of freedom”. Mirabeau was the first of these great men, followed by Voltaire, whose ashes were transferred to the Pantheon on 21 July 1791 in a magnificent ceremony.

During this period the building underwent a series of alterations to create a more austere atmosphere in keeping with its new vocation, including removing the bells, walling up the windows and replacing some religious low-relief sculptures by works exalting patriotic virtues.

The upheavals of the Revolution

Jean-Jacques Rousseau by M. Quentin de La Tour

Until 1795, the various political upheavals of the revolutionary period lead to a succession of “Pantheonisations” and “Depantheonisations”. Marat entered the Pantheon in 1794, on the same day that Mirabeau was evicted, accused of treachery. The following year, Marat’s remains were ejected whilst the precursor of revolutionary ideals, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, was welcomed.

In February 1795, a new decree imposed a 10-year waiting period between a person’s death and their inhumation at the Pantheon.

An imperial temple

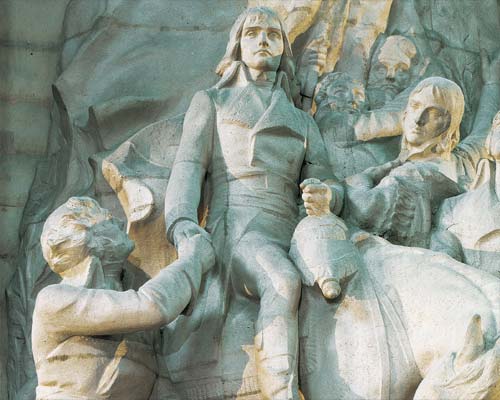

Bonaparte, detail from the monument to the glory of the generals of the Revolution , de P.-J.-B Gasc

An imperial decree issued on 20 February 1806 re-established the building’s religious vocation. Only the crypt retained its civic role. With its double function, several religious ceremonies took place at the Pantheon during the imperial commemorations, whilst the crypt continued to receive the remains of great men.

Until the fall of his regime in 1815, Napoleon pantheonised numerous individuals. Over nine years, forty-one prominent figures from his regime were inhumed in the crypt. These were generally lawyers, scientists, military men or dignitaries who had served the State. Under the Restoration, the Pantheon was returned entirely to the Catholic Church. The only remains to be inhumed here after the cult of great men was abandoned were those of Soufflot, the monument’s architect, in 1829.

A republican temple

The Pantheon in 1835, by F.-E. Villeret

The Revolution of 1830 re-converted the monument into the Pantheon, before it was once again returned to the Church in 1851 under Napoleon III. From 1873 onwards the decision was taken to adorn the Pantheon with paintings and sculptures representing great religious and monarchic figures of the history of France.

The death of Victor Hugo in 1885 was the event that sealed the long-term republican vocation of the Pantheon. A million people accompanied the writer’s coffin to its final resting place. Under the Third Republic, many politicians (Jaures), writers (Zola) and scientists (Berthelot) received the posthumous honour of pantheonisation, sometimes causing controversy, such as Emile Zola in 1908.

Perpetuating the vocation

The peristyle during the transfer of the ashes of Pierre and Marie Curie in 1995.

The practice of pantheonisation continued under the Fourth and Fifth Republics at varying rates depending on the Head of State. In 1964, the pantheonisation of Jean Moulin was a memorable event presided by General De Gaulle. The speech made by Andre Malraux, who was himself pantheonised by Jacques Chirac in 1996, has remained engraved on people’s memories. At his investiture in 1981, Francois Mitterrand placed three symbolic roses in the crypt, a solemn gesture to symbolise the connection between the State and the Pantheon.

Since the beginning of the Fifth Republic, the decree authorising the transfer of a body to the Pantheon must be signed by the Head of State at the request of a committee of prominent people or their descendants, who by their actions, must have defended republican values or have contributed to the progress of humanity.