History of the Louvre

From Chateau to Museum

The Louvre, in its successive architectural metamorphoses, has dominated central Paris since the late 12th century. Built on the city's western edge, the original structure was gradually engulfed as the city grew. The dark fortress of the early days was transformed into the modernized dwelling of Francois I and, later, the sumptuous palace of the Sun King, Louis XIV. Here we explore the history of this extraordinary edifice and of the museum that has occupied it since 1793.

The Middle Ages

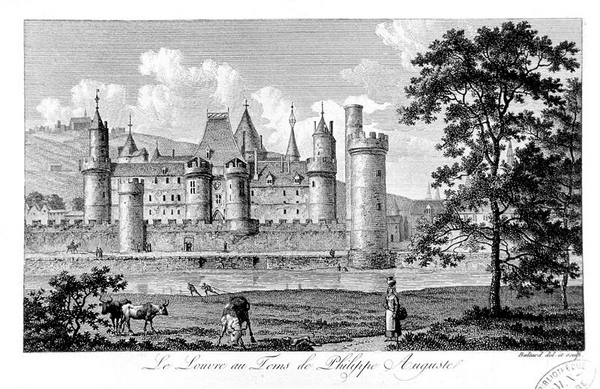

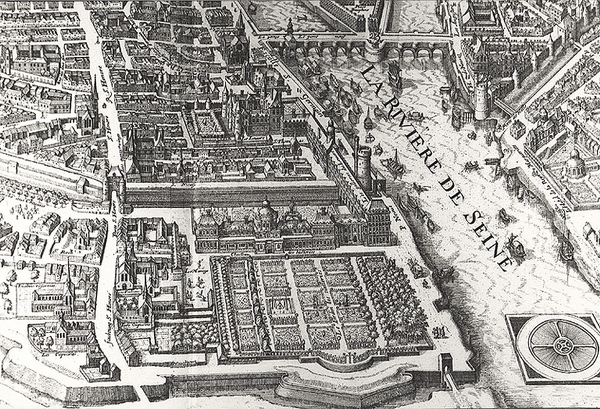

During the forty-three-year reign of Philippe Auguste (1180–1223), the power and influence of the French monarchy grew considerably, both inside and outside the kingdom. In 1190, a rampart was built around Paris, which was Europe’s biggest city at the time. To protect the capital from the Anglo-Norman threat, the king decided to reinforce its defenses with a fortress, which came to be known as the Louvre. It was built to the west of the city, on the banks of the Seine.

1190–1202 Construction of the fortress and keep under Philippe Auguste

Philippe Auguste's fortress of 1190 was not a royal residence but a sizable arsenal comprising a moated quadrilateral (seventy-eight by seventy-two meters) with round bastions at each corner, and at the center of the north and west walls. Defensive towers flanked narrow gates in the south and east walls. At the center of this complex stood the massive keep, the Grosse Tour (fifteen meters in diameter and thirty meters high). Two inner buildings abutted the outer walls on the west and south sides.

1230–40 The vaulting of the Salle Basse in the western section

The Salle Basse (Lower Hall) is all that remains today of the Louvre’s medieval interior. Its original function is unknown. The vaulted ceiling (now destroyed) rested on two columns at the center of the hall and on supporting walls. The vaulting, columns, and corbels that can be seen today date from 1230–40 and were added to the old masonry.

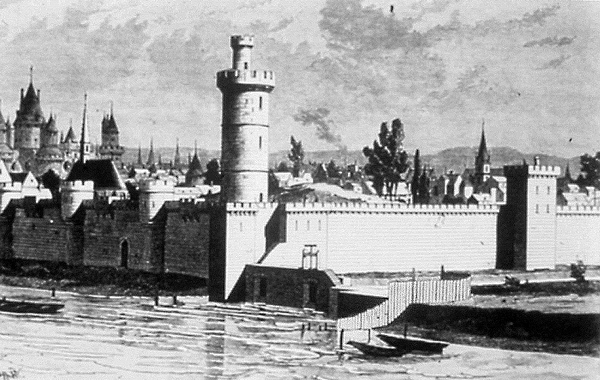

1358–65 New ramparts by Etienne Marcel and Charles V

In the mid-14th century, Paris spread far beyond Philippe Auguste’s original wall. With the onset of the Hundred Years' War, further defenses were needed for the French capital. Etienne Marcel, provost of the merchants of Paris, instigated the construction of an earth rampart (1356–58), which was continued and developed under Charles V. The new defenses encompassed the neighborhoods on the right bank of the Seine. Enclosed within the expanding city, the Louvre lost its defensive function.

1364–69 Transformation by Raymond du Temple

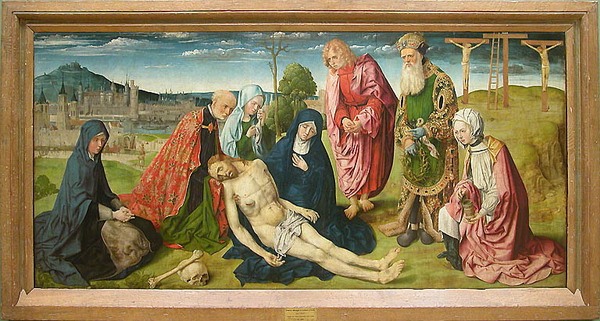

In 1364, Raymond du Temple, architect to Charles V, began transforming the old fortress into a splendid royal residence. Contemporary miniatures and paintings contain marvelous images of ornately decorated rooftops. Apartments around the central court featured large, elaborately-carved windows. A majestic spiral staircase, the “grande vis,” served the upper floors of the new buildings, and a pleasure garden was created at the north end. The sumptuous interiors were decorated with sculptures, tapestries, and paneling.

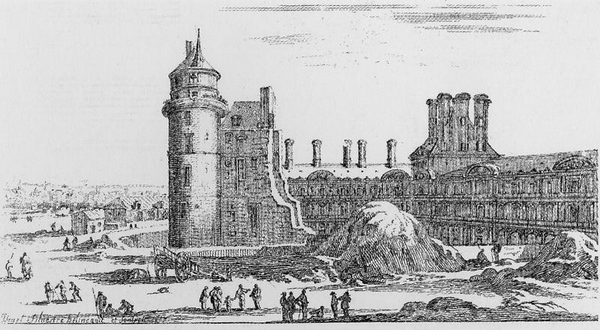

1527–28 Destruction of the keep

After the death of Charles VI, the Louvre slumbered for a century until 1527, when Francois I decided to take up residence in Paris. The Grosse Tour (the medieval keep) was demolished, affording still more light and space. The medieval Louvre gave way to a Renaissance palace.

From the Louvre to the Tuileries

The demolition of the Grosse Tour marked the beginning of a new phase of building work that would continue through to the reign of Louis XIV. The transformation of Francois I’s chateau continued under Henri II and his sons. However, the construction of the Tuileries palace some 500 meters to the west led to a rethinking of the site. Ambitious royal plans to link the two buildings culminated in the creation of the Grande Galerie.

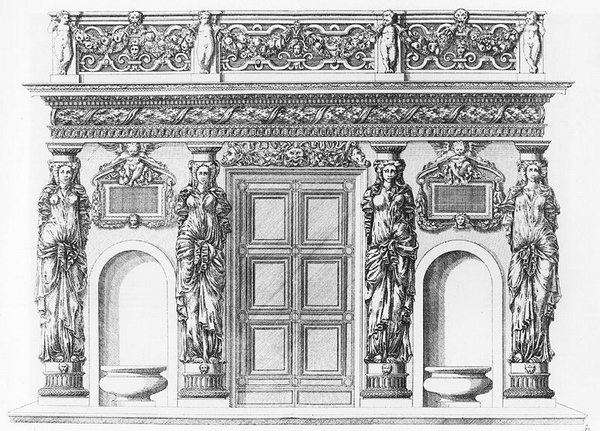

1546–60 The Lescot wing, the Pavillon du Roi, and the south wing

Even after its transformation, Charles V’s chateau was inadequate for the needs of Francois I, who ordered the construction of new buildings at the Louvre in 1546. The medieval west wing was demolished and replaced with Renaissance-style buildings designed by Pierre Lescot and decorated by Jean Goujon. The work begun under Francois I was completed by Henri II, who created the Salle des Caryatides (Hall of the Caryatids) on the ground floor and built a new wing following the demolition of the castle's medieval south wing. The Pavillon du Roi (King’s Pavilion) was built at the junction of the new buildings and housed the king’s private apartments on the first floor. The new, uniform facades established the Parisian Renaissance style. Their decoration was finally completed under Henri IV.

1564–72 Construction of the Tuileries palace

In the second half of the 16th century, the Louvre was an astonishing mixture of new buildings, work in progress, and half-ruined structures over 200 years old. Dissatisfied with its lack of comfort, and with the noise and smell of the city, Henri II's widow Catherine de Medicis ordered the building of a new residence a short distance to the west. Plans for the Tuileries palace were drawn up by Philibert Delorme in 1564, but work was discontinued a few years later.

1566 Start of work on the Petite Galerie

In 1566, Charles IX began building the ground floor of the Petite Galerie, a small wing intended to serve as a starting point for a long corridor connecting the Louvre to the Tuileries along the banks of the Seine. The plan to create a link between the two palaces was beginning to take shape.

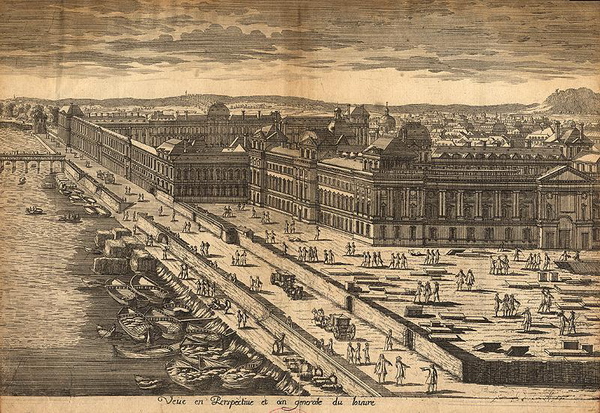

1595–1610 Construction of the Grande Galerie

Henri IV built the Galerie du Bord de l’Eau (Waterside Gallery) between 1595 and 1610. Also known as the Grande Galerie, the long passage provided a direct link from the royal apartments in the Louvre to the Tuileries palace, ending with the Pavillon de Flore. To avoid excessive monotony along its 450-meter facade, two architects were hired: Louis Metezeau for the east end and Jacques II Androuet du Cerceau for the west. During the same period, the Galerie des Rois (Kings' Gallery) was built on top of the Petite Galerie.

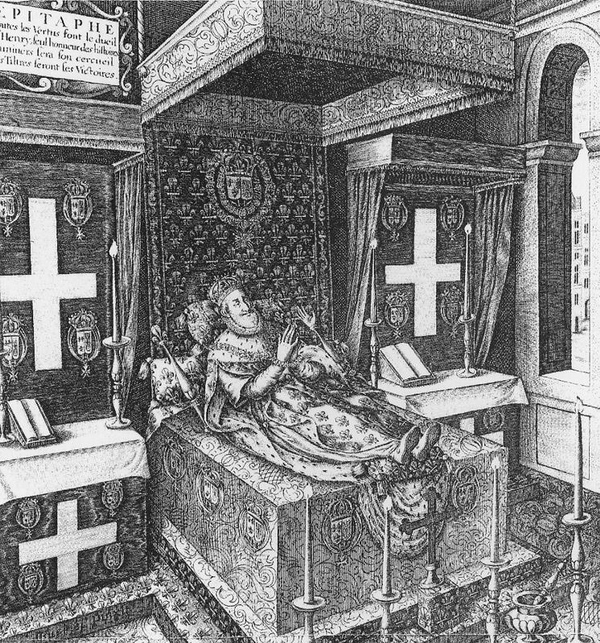

1610 Assassination of Henri IV

Henri IV's tragic death on May 14, 1610, left his works unfinished: the main shell of the Grande Galerie was complete and roofed, but the interior remained undecorated. His successor, Louis XIII, acceded to the throne when he was only nine years old. Work begun by him fifteen years later was completed under Louis XIV.

The Classical Period

The reigns of Louis XIII and Louis XIV had a major impact on the Louvre and Tuileries palaces. The extension of the west wing of the Cour Carree under Louis XIII marked the beginning of an ambitious program of work that would be completed by Louis XIV and added to by Louis XV, resulting in the Louvre that we see today. However, following the completion of Versailles, royal interest in the palace waned, plunging the Louvre into a new period of dormancy.

1624 Resumption of work under Louis XIII

In 1625, after over ten years of inactivity, Louis XIII decided to resume construction work and carry out the so-called Grand Dessein (Grand Design) envisaged by Henri IV. Louis XIII ordered the demolition of part of the north wing of the medieval Louvre and its replacement by a continuation of the Lescot wing, with identical decoration and detail.

1639 The Pavillon de l'Horloge and the Lemercier wing

Between the new building and the old one, the architect Jacques Lemercier installed the monumental Pavillon de l’Horloge (Clock Pavilion), now known as the Pavillon Sully. With its steeply pitched roofs and imposing top story decorated with powerful caryatids, the building dominates the Louvre complex and serves as the model for the palace's other pavilions.

1655–59 Decoration of Anne of Austria's summer apartments

Between 1655 and 1658, Anne of Austria, the queen mother and regent during Louis XIV's childhood, created a suite of private apartments on the ground floor of the Petite Galerie. The six interconnecting rooms (a common arrangement at the time) comprised a large salon, anteroom, and vestibule, a grand cabinet (study or private sitting room), a bedchamber, and a petit cabinet overlooking the Seine. The decoration was carried out by the Italian Romanelli (frescoes and ceilings) and Anguier (stucco).

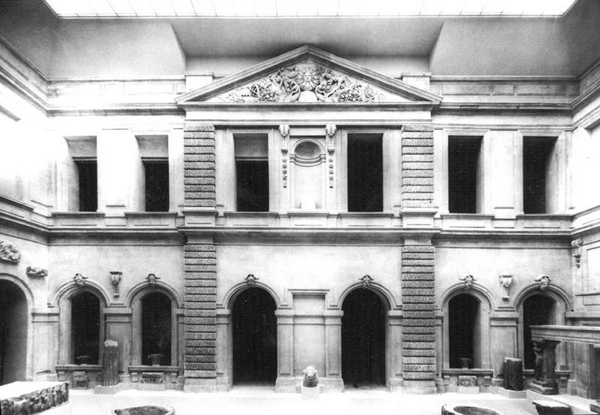

1660–64 Completion of the Cour Carree and the Cour du Sphinx

In 1660 Louis Le Vau was appointed to oversee the completion of the Louvre. This entailed a new facade for the Petite Galerie, the completion of the north wing of the Cour Carree, and, between 1661 and 1663, the extension of the south wing, including two new pavilions—one at the eastern end, symmetrical to the Renaissance Pavillon du Roi, and one in the center. In 1668, Le Vau doubled the width of the palace and constructed a new facade overlooking the Seine. The last vestiges of the medieval Louvre were demolished.

1662–64 The Galerie d'Apollon

On February 6, 1661, fire ravaged the upper story of the Petite Galerie. While Le Vau oversaw the reconstruction work, the Sun King, Louis XIV, commissioned Charles Le Brun to execute decorative paintings evoking the passage of the sun represented by the Roman sun god Apollo. The decoration was left unfinished, but includes three ceiling panels by Le Brun (begun in 1663) and a number of large-scale stucco sculptures.

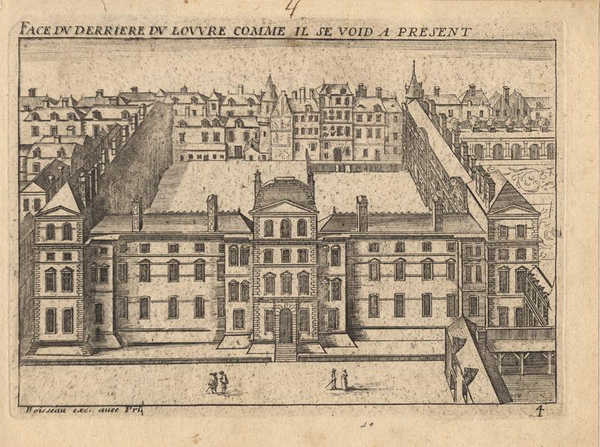

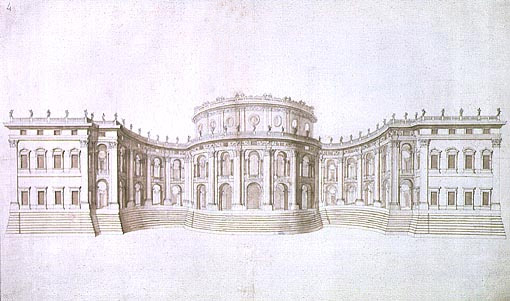

1665 Designs by Bernini

In 1665, Louis XIV invited the Italian sculptor and architect Bernini to work on the eastern wing of the Cour Carree, the planned site of a grandiose new entrance to the royal residence. Bernini submitted two projects, but Louis called a halt to construction work, and neither was completed.

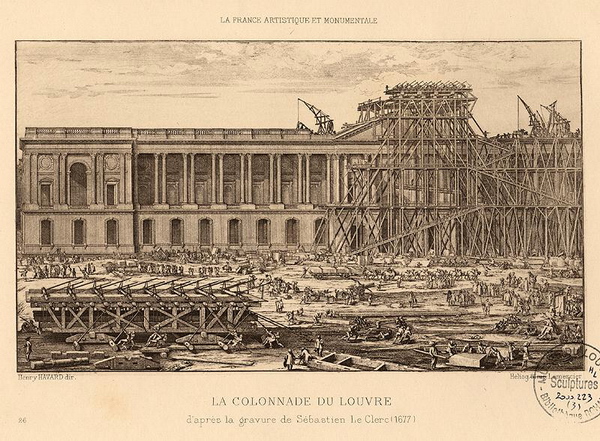

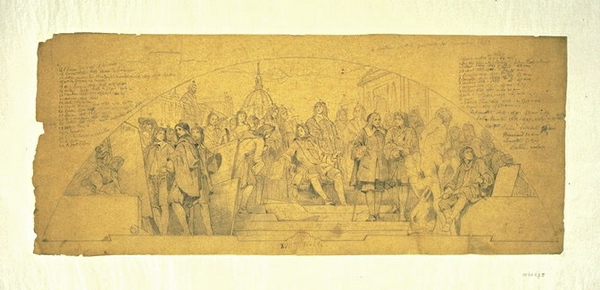

1667–72 The Colonnade

In 1667, a committee that included the physician Claude Perrault designed the celebrated Colonnade, a monumental facade with a peristyle of double columns occupying the entire upper story. Building was stopped in 1672, when Louis XIV moved to Versailles, leaving the project unfinished.

1674 Louis XIV leaves for Versailles

As work progressed at Versailles, Louis XIV's permanent residence from 1672, Jean-Baptiste Colbert (controller general of finances) called a halt to work at the Louvre. The buildings of the Cour Carree were left unroofed and exposed to the elements. They remained so for nearly a century.

1692 A new role for the abandoned palace

In 1692, Louis XIV ordered the creation of a gallery of antique sculpture in the Salle des Caryatides. In the same year, the deserted palace received new occupants: the Academie Francaise was followed by the Academie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres and the Academie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, which remained until 1792. In 1699, the latter held the first of a long series of salons, drawing large crowds.

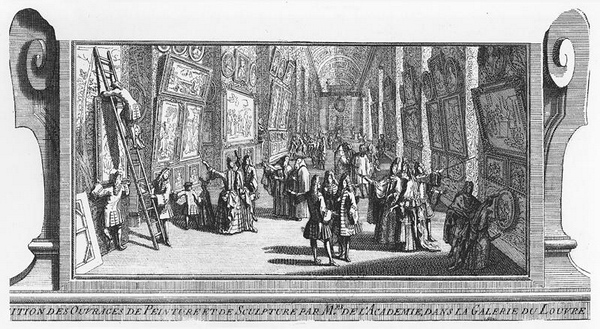

1699 The birth of the Paris Salon

In 1699, the artist members of the Academie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (founded in 1648) held their first exhibition at the Louvre, in the Grande Galerie. From 1725, the event was held in the Salon Carre (Square Salon), near the Academie's offices. The show was henceforth known as the “Salon.”

1756 Resumption of work under Louis XV

In 1756, Louis XV ordered the resumption of construction work at the Louvre. The wings begun under Louis XIV were partially completed, and the north, east, and south sides of the Cour Carree were finally roofed. At the same time, the monumentality of Perrault’s Colonnade could at last be properly appreciated thanks to the demolition of buildings at its foot. A complex of ancillary buildings in the Cour Carree was also razed.

1791 A monument to science and the arts

In 1791, the revolutionary Assemblee Nationale decreed that the “Louvre and the Tuileries together will be a national palace to house the king and for gathering together all the monuments of the sciences and the arts.''

1793 Opening of the Museum Central des Arts

The Museum Central des Arts opened its doors on August 10, 1793. Under the authority of the Minister of the Interior, its first governors were the painters Hubert Robert, Fragonard, and Vincent, the sculptor Pajou, and the architect de Wailly. Admission was free, with artists given priority over the general public, who were admitted on weekends only. The works, mostly paintings from the collections of the French royal family and aristocrats who had fled abroad, were displayed in the Salon Carre and the Grande Galerie.

From Palace to Museum

With the Revolution, the Louvre entered a phase of intensive transformation. For three years, Louis XVI lived in the Tuileries palace, alongside the Convention Nationale. In 1793 the Museum Central des Arts opened to the public in the Grande Galerie and the Salon Carre, from where the collections gradually spread to take over the building. Anne of Austria’s apartments housed the antique sculpture galleries, and further rooms and exhibition spaces were opened under Charles X.

1798 Artworks from Italy: the Musee Napoleon

Through the treaties of Tolentino and Campo Formio, France acquired numerous paintings and antiquities from the Vatican and the Venetian republic. These were enriched by spoils from Napoleon I's conquests. The museum, of which Dominique-Vivant Denon had become director in 1802, was renamed the Musee Napoleon in 1803. A bust of the emperor by Bartolini was installed over the entrance. After the fall of the empire in 1815, each nation reclaimed its treasures and the museum was disbanded.

1800 Antique marble statues in the Petite Galerie

On November 9, 1800, the first anniversary of the coup d'etat of 18 Brumaire VII, Napoleon and Josephine inaugurated the Musee des Antiques in the former apartments of Anne of Austria on the ground floor of the Petite Galerie (the upper floors were too weak to support the weight of the marble sculptures). Here, visitors could admire pieces from the Vatican, the Capitoline museum, and Florence, together with the collections of the French royal family and emigre aristocrats.

1804–11 Enlargement and embellishment under Fontaine

The enlargement and embellishment of the palace was entrusted to the architect Fontaine. A new monumental staircase served the Salon Carre and the Grande Galerie, which was bathed in daylight from new windows overhead. The facades facing the Cour Carree were homogenized, and staircases were raised at each end of the Colonnade, whose central pavilion received a bronze door and a tympanum. A new north wing progressed from the Tuileries toward the Louvre along the rue de Rivoli.

1806–7 The Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel

In 1806, Percier and Fontaine built a small triumphal arch aligned with the Pavillon de l’Horloge and the central pavilion of the Tuileries. Inaugurated in 1808, it was decorated with reliefs and statues by Denon celebrating French military victories. On the top, Denon installed the four celebrated antique bronze horses from the facade of Saint Mark's Basilica in Venice. The horses were returned to Venice in 1815.

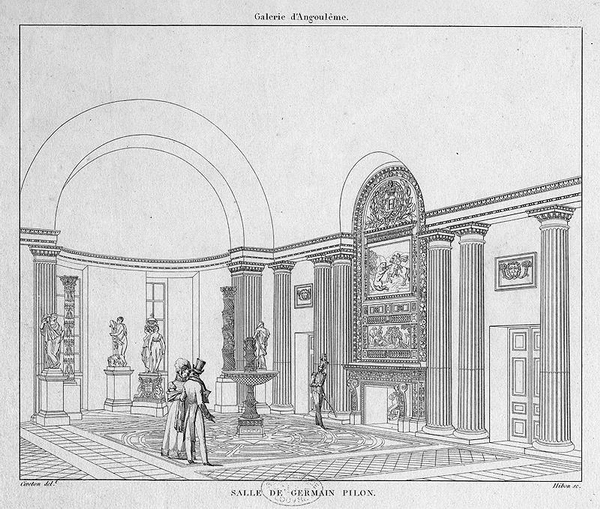

1824 The Musee de la Sculpture Moderne

In 1824, the Musee de Sculpture Moderne was created in the Galerie d'Angouleme on the ground floor of the Cour Carree’s west wing, between the Pavillon de l'Horloge and the Beauvais wing. Five rooms decorated by Fontaine displayed sculptures from the Musee des Monuments Francais, as well as from Versailles.

1826 Champollion becomes curator of Egyptian antiquities

Jean-Francois Champollion was the founder of modern scientific Egyptology. In 1822 he discovered the principles of hieroglyphic writing, and later published articles on the Rosetta Stone (now in the British Museum, London) and the transcription of hieroglyphics into Greek. After overseeing the establishment of the Egyptian museum in Turin (1824), he became the first curator of the Louvre’s new Department of Egyptian Antiquities on May 15, 1826.

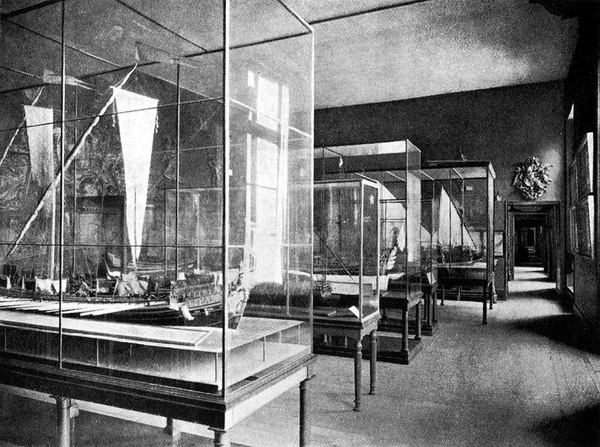

1827 The Musee Charles X and the Musee de la Marine

In 1827, the Musee Charles X was inaugurated on the first floor of the Cour Carree’s south wing. Its collections included Egyptian antiquities, ancient bronzes, Etruscan vases, and medieval and Renaissance decorative arts. The ceilings featured decorative paintings by the leading official artists of the day. In the same year, the Musee de la Marine was installed on the first floor and, later, the second floor of the Cour Carree’s north wing, where it remained until 1943.

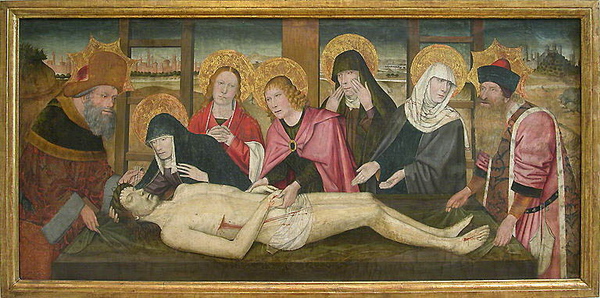

1837–48 Spanish gallery created under Louis-Philippe

Rarely seen in France before the Revolution, Spanish art was revealed to the public with the opening of Louis-Philippe’s Spanish gallery. Exhibited in the Louvre from 1838 to 1848, before being sold in London in 1853, the collection of over 400 paintings was a major influence on artists such as Corot and Manet.

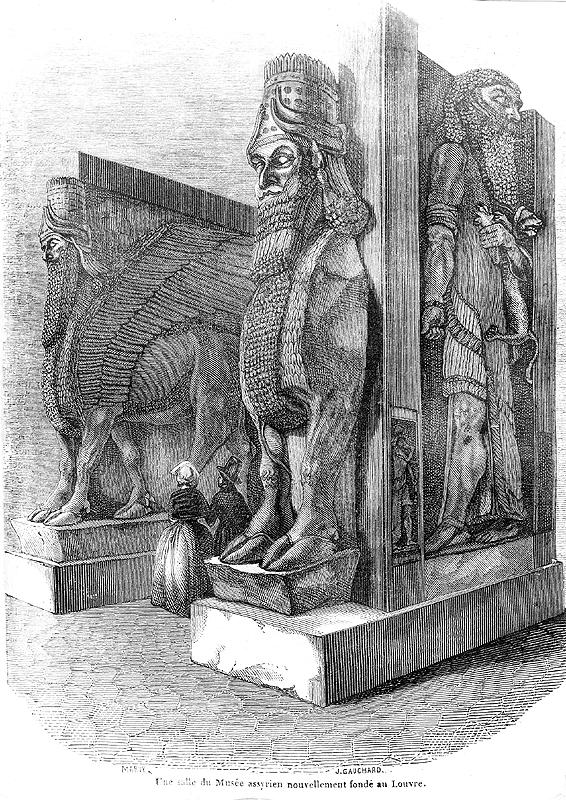

1849 Opening of the Assyrian Museum

On May 1, 1847, Europe’s first museum of Assyrian art was inaugurated in two galleries in the north wing of the Cour Carree. It was the result of shipments of material made by Paul-Emile Botta (1802–1870), who served as French consul in Mosul.

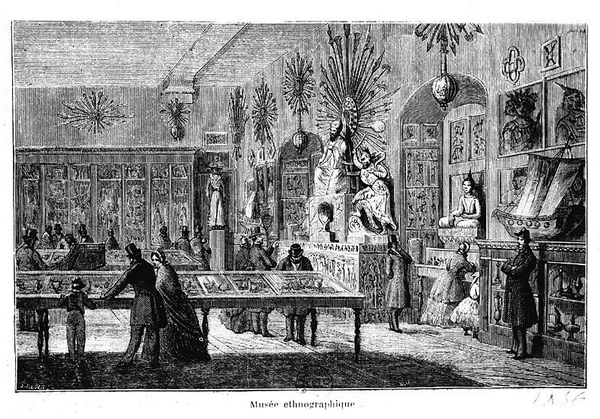

1850 The opening of the Mexican, Algerian, and ethnographic museums

The fascination with exotic worlds, and especially with the scientific study of traditional crafts and folk art, led in 1850 to the creation of the Musee Mexicain on the ground floor of the Cour Carree, together with the Algerian and ethnographic museums on the second floor of the Pavillon de Beauvais, in the north wing of the Cour Carree.

1848–51 Decorative work by Delacroix and Duban

Three important new galleries featuring major decorative schemes were completed under the prince-president Louis-Napoleon. In 1848, Felix Duban was commissioned to restore the Galerie d'Apollon. The decoration was completed in 1851 with the installation of the central ceiling panel by Delacroix. Duban also restored the Salle des Sept-Cheminees (Hall of Seven Chimneys), with its impressively decorated ceiling, and the Salon Carree.

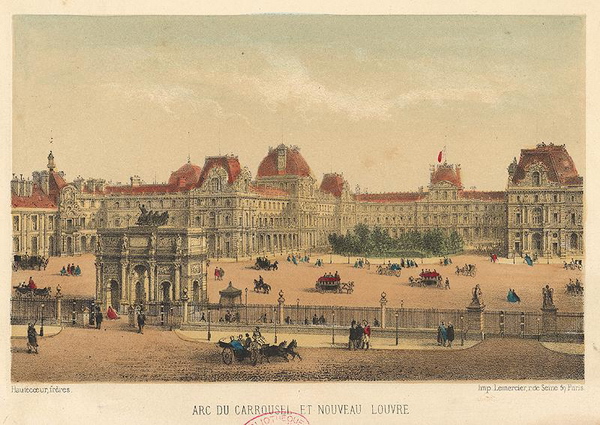

1852–57 The new Louvre

Napoleon III commissioned Visconti and (following his death) Lefuel to finish the north wing linking the Louvre and the Tuileries. Central to the design was the completion of new buildings along the rue de Rivoli, extending the existing wings built under Napoleon I and Louis XVIII, and the building of two new wings with inner courtyards. The Cour Napoleon, at the heart of this complex, was finished in 1857. The interior decoration was completed in 1861.

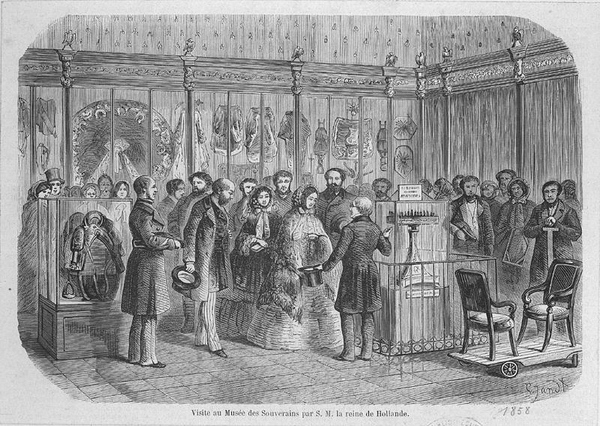

1852–70 The Musee des Souverains

On February 15, 1852, Louis-Napoleon opened the Musee des Souverains on the first floor of the Colonnade. The museum displayed treasures from France’s royal dynasties, from Childeric I to Napoleon, and constituted a spectacular addition to the Louvre's collection of decorative arts.

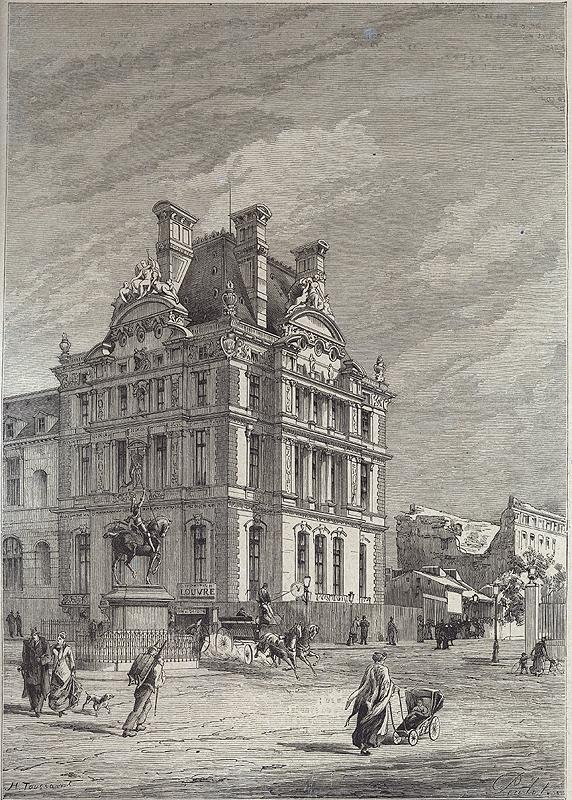

1861–69 The Pavillon de Flore and the Grands Guichets

In 1861, the emperor asked Lefuel to rebuild the west end of the decrepit Grande Galerie and the Pavillon de Flore. Henri IV's buildings were partially demolished and replaced with structures matching those to the east by Metezeau. The Grande Galerie was now more unified, but at the expense of its creators' intended variety. At the center of the new facade facing the Seine, Lefuel built the monumental Grands Guichets (ticket windows) adorned with an equestrian statue of Napoleon III.

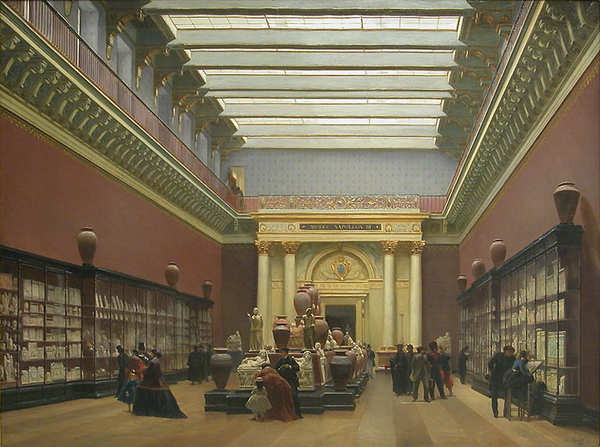

1863 Musee Napoleon III

The Louvre’s collections were considerably enriched during the Second Empire, thanks in large part to the acquisition of the collection of the marquis Campana in 1861, which consisted of 11,385 paintings, objets d'art, sculptures, and antiquities. The collection became the Musee Napoleon III in 1863. A number of items form a major part of the Louvre's collections of Greek pottery and Etruscan antiquities displayed in the Galerie Campana.

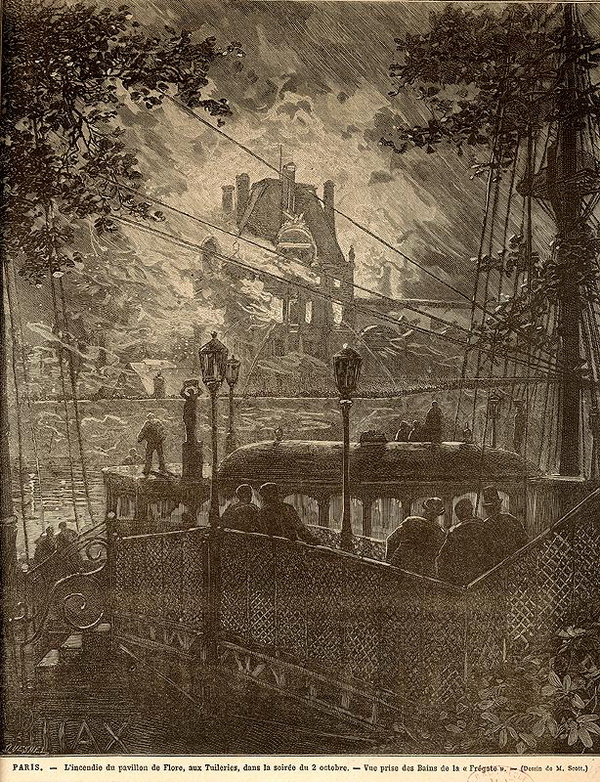

1871 The burning of the Tuileries

In May 1871, during the last days of the Paris Commune, the army was poised to retake the city. The Communards raced to destroy the Hotel de Ville (city hall), the Cour des Comptes (the seat of France's public finance watchdog), and the Tuileries palace, a potent symbol of monarchy. The resulting fire gutted the palace buildings and threatened the Louvre. The ruins of the Tuileries were demolished, after lengthy controversy, in 1883.

The Grand Louvre

The demolition of the Tuileries in 1882 marked the birth of the modern Louvre. The palace ceased to be the seat of power and was devoted almost entirely to culture. Only the Finance Ministry, provisionally installed in the Richelieu wing after the Commune, remained. Slowly but surely, the museum began to take over the whole of the vast complex of buildings.

1875–78 The rebuilding of the Flore and Marsan pavilions

Restoration of the Flore and Marsan pavilions (at either end of the former Tuileries palace) began in 1874. The Pavillon de Flore served as the model for the renovation of the Pavillon de Marsan, which replaced the building by Le Vau. The width of the north wing along the rue de Rivoli was doubled.

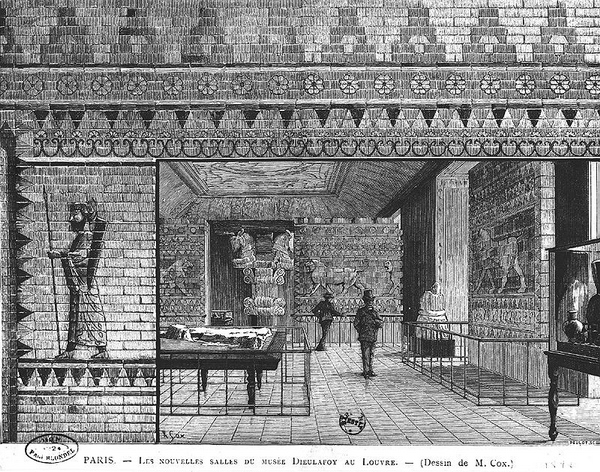

1888 The inauguration of the Susa galleries

Excavations led by the French archaeologist Marcel Dieulafoy at Susa, in Iran, yielded a number of important discoveries, which were put on display in new rooms at the museum in 1888. This new collection of exhibits represented a major addition to the recently created Department of Near Eastern Antiquities.

1905 The inauguration of the Musee des Arts Decoratifs

Created in the wake of the 19th-century Expositions Universelles in Paris, and formerly housed in the Palais de l’Industrie and the Pavillon de Flore, the Musee des Arts Decoratifs was inaugurated on May 29, 1905. Managed by the Union Centrale des Arts Decoratifs (UCAD), its collections were displayed in the Louvre's rue de Rivoli wing, between the north entrance to the museum and the Pavillon de Marsan.

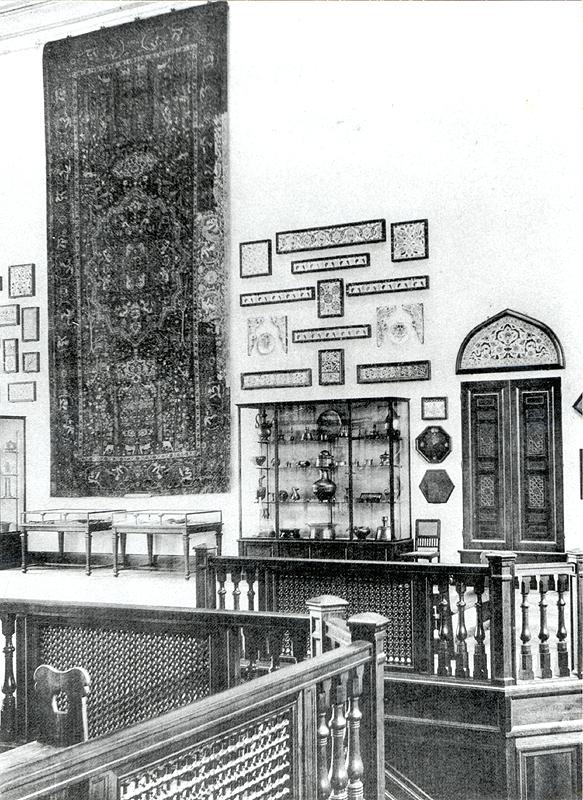

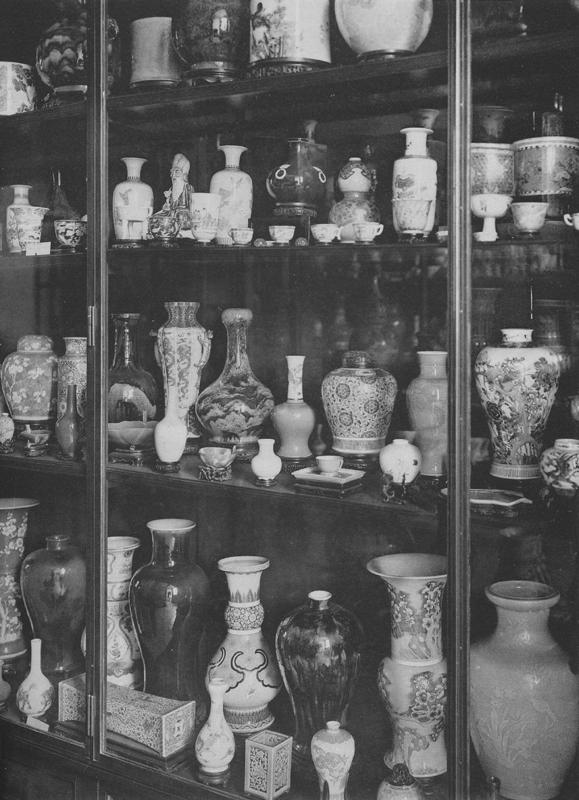

1922 The opening of the first Islamic gallery

The museum's holdings in Islamic art were originally scattered throughout the rooms devoted to the decorative arts. The collection was considerably enriched in 1912 by the bequest of Baroness Delort de Gleon. Plans for a single display led, in 1922, to the opening of a gallery devoted to the Islamic East in the dome of the Pavillon de l’Horloge.

1932–38 The plan of 1926

In 1926, France's director of national museums, Henri Verne, launched an ambitious plan to extend the exhibition space at the Louvre. Work began in 1930 and continued during and after World War II. The Cour du Sphinx was given a glazed roof for the display of antique sculpture, while new rooms of European sculpture in the Flore wing, and of objets d’art and paintings in the Cour Carree were opened. The galleries of Egyptian and Near Eastern antiquities were completely refurbished.

1939–45 World War II: Evacuation and closure of the museum

At the outbreak of war in September 1939 the museum's collections were evacuated, with the exception of the heaviest pieces, which were protected with sandbags. The works were initially deposited at the Chateau de Chambord in the Loire valley, before being dispersed to numerous other sites, mostly chateaus. For safety reasons, many works were moved several times during the war. Although mostly empty but for plaster casts, the Louvre reopened under the Occupation, in September 1940.

1943 The transfer of the Musee de la Marine

The collections continued to expand under the impetus of Henri Verne's plans, leading the Musee de la Marine to seek larger premises. Run since 1919 by the History Department of the French Admiralty, the museum was transferred to a wing of the new Palais de Chaillot in 1943.

1945 The Asian collections move to the Musee Guimet

In 1945 a new plan for the reorganization of France's national art collections was drawn up. The Asian collections, which had until then been housed at the Louvre (notably the donations of Isaac de Camondo, Raymond Koechlin, and Grandidier, together with the Marteau bequest), were transferred to the Musee Guimet on place d’Iena, in Paris.

1947 The inauguration of the Jeu de Paume

The former Jeu de Paume (games court) in the northeast corner of the Tuileries gardens (1861) was used for a variety of exhibitions before being annexed to the Louvre in 1947 as the Musee de l'Impressionisme. Faced with increasingly cramped conditions, the museum closed on August 18, 1986, and its expanding collections were transferred to the new Musee d’Orsay.

1953 The Braque ceiling

The former royal antechamber retained its original, richly-carved ceiling, executed in 1557 by the wood-carver Scibec de Carpi. The Cubist painter Georges Braque (1882–1963) was commissioned to produce a series of three ceiling paintings within Carpi's design. The resulting decorative design, The Birds, was inaugurated in 1953.

1961–68 The departure of the Finance Ministry

In 1961, the Pavillon de Flore was vacated by the French Finance Ministry. The museum's Department of Sculptures was moved to the ground floor and basement, with paintings on the first floor of the western part of the Grande Galerie and drawings on the second floor. Restoration laboratories and workshops were set up on the upper floors. The 1968 exhibition of European Gothic art marked the official incoporation of these new spaces into the Louvre proper.

1964 A dry moat in front of the Colonnade

In 1964, the minister of culture, Andre Malraux, ordered the digging of a dry moat in front of Perrault’s Colonnade. Although a characteristic feature of French classical architecture, the moat appears on none of the building's original plans and was probably never envisaged by Louis XIV.

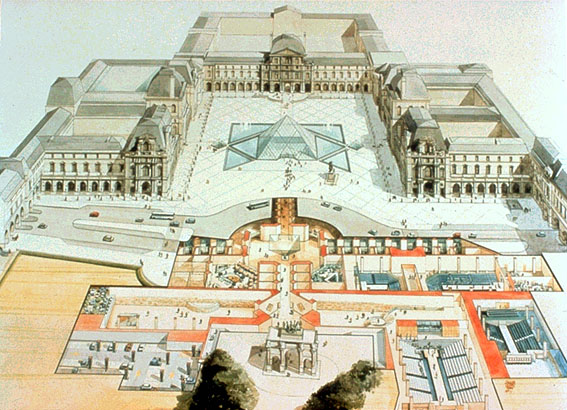

1981 The launch of the Grand Louvre project

The need to improve the museum’s displays and provide better amenities for visitors became increasingly pressing. On September 26, 1981, President Francois Mitterrand announced a plan to restore the Louvre palace in its entirety to its function as a museum. The Finance Ministry, which still occupied the Richelieu wing, was transferred to new premises, and the Grand Louvre project, which would entail a complete reorganization of the museum, was launched.

1983 The EPGL and the appointment of I. M. Pei

On November 2, 1983, the Etablissement Public du Grand Louvre (EPGL) was given overall control of the project. The extension and modernization of the Louvre were entrusted to the Chinese-American architect Ieoh Ming Pei, whose many buildings included the new wing of the National Gallery in Washington D.C. Archaeological excavations were undertaken before work began on the new spaces beneath the Cour Napoleon and the construction of the Pyramid.

1986 The inauguration of the Musee d'Orsay

The Musee d’Orsay was inaugurated on December 9, 1986, in Victor Laloux's renovated 1900 train station. The new museum encompassed the various movements that emerged in the second half of the 19th century, from 1848 to the beginnings of cubism. It provided a transition between the collections of the Louvre (from which it incorporated works by artists born between 1820 and 1870) and those of the Musee Nationale d'Art Moderne. Works formerly displayed at the Jeu de Paume were also transferred to the Musee d'Orsay.

1989 The opening of the Pyramid

The glass Pyramid built by I. M. Pei was inaugurated on March 30, 1989. Rising from the center of the Cour Napoleon, it is the focal point of the museum's main axes of circulation and also serves as an entrance to the large reception hall beneath. From here, visitors can also reach the temporary exhibition areas, displays on the history of the palace and museum, Charles V's original moat, an auditorium, and public amenities (coat check, bookshop, cafeteria, restaurant).

1993 New exhibition spaces are opened

On January 1, 1993, the Louvre became an Etablissement Public linked to the Ministry of Culture, thereby acquiring greater autonomy. The same year, the renovated Richelieu wing was opened, representing the biggest single expansion in the museum's history. Glazed roofs over three inner courtyards created new spaces for the display of monumental sculpture, the departments of paintings and decorative arts expanded their exhibition space, and rooms were set aside for the collection of Islamic art. The Galeries du Carrousel (a new underground shopping mall and parking garage) opened soon afterward.

1997 Phase two of the Grand Louvre project

In 1997, major new developments continued around the Cour Carree, with the inauguration of the Sackler wing (Near Eastern antiquities) and, most importantly, the opening of two completely refurbished floors housing the Department of Egyptian Antiquities, which doubled its exhibition space. Work also began on a scheme to refurbish the Salle des Etats and to create three new galleries of antique art (the “salles des trois antiques”) beneath the Cour Visconti.

1999 The opening of the Pavillon des Sessions

In 1996, the French president, Jacques Chirac, announced the creation of a national museum of tribal and aboriginal art. In addition, selected masterpieces from Africa, Asia, Oceania, and the Americas were to be shown at the Louvre. These were installed on the ground floor of the former Pavillon des Sessions, in galleries refurbished by the architect J. M. Wilmotte. Inaugurated in April 2000, these galleries are a satellite of the future Musee du Quai Branly, scheduled to open in 2006.