Padova - Basilica di sant'Antonio

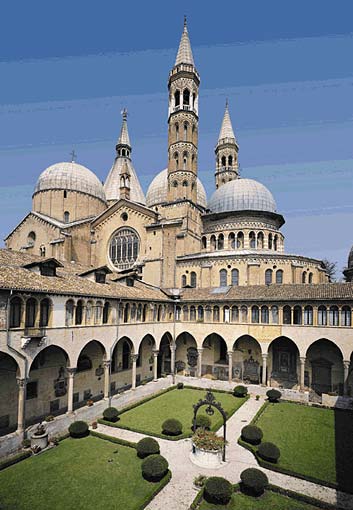

The exterior

The actual Basilica is largely the result of three different reconstructions, which took place over a period of about 70 years: 1238-1310.

In St. Anthony's time there was the little church Santa Maria Mater Domini, which was then integrated into the Basilica and is now the Chapel of the Black Madonna. Next to this, in 1229, the Friary sprang up, which was probably founded by St. Anthony himself.

St. Anthony died in 1231 in Arcella, in the north of the city where a Clarisse monastery then stood, his body - according his own wishes - was transported and buried in the little church Santa Maria Mater Domini.

The construction of the first nucleus of the Basilica, a Franciscan church with only a single nave and a short transept, began in 1238; two lateral naves were added and it was eventually transformed into the amazing structure that we admire today.

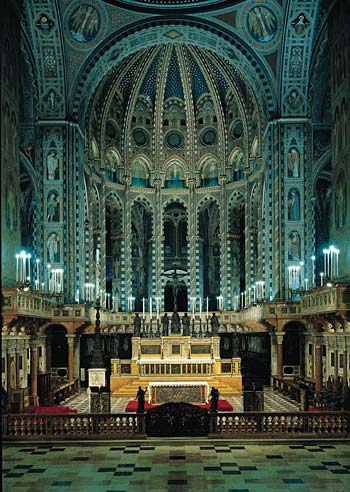

The inside

Let's begin with the central nave. You can notice straightaway that the architecture is quite Gothic, and that there are two distinct parts: the nave (where we are now) and the apse beyond the transept. This is not only because the latter is completely frescoed but also because there is a different Gothic style.

The nave area appears quite spacious marked by two solemn arches on either side. Above these, on both the right and left there is a balcony, which accompanies the central nave, entering the transept.

The numerous funeral monuments are as equally striking as the remnants of decorations and paintings that cover pillars and other spaces and mostly originate from the XV-XVII centuries. Nowadays, we often prefer to see churches cleaned up of this encrustation of the past.

However, we must not undervalue the artistic value of these monuments nor the fact that they represent an interesting cross-section of the social and cultural life of the city and region. Still, these funeral monuments do not interest the majority of visitors.

Before leaving the central nave, please observe the great fresco by Pietro Annigoni, finished in 1985 on the counter facade, depicting St. Anthony preaching from the walnut tree. This episode from his life took place in Camposampiero (Padua) where the Saint, just before his death, spent a brief period of rest and reflection (from the second half of May to 13 June 1231).

The Saint indicated the Gospel as a source of life and light to the people (simple or ill, indifferent or curious; an element of counterpoint can be found in the three children) and to his friars (Blessed Luca Belludi, St. Anthony's successor, is at the foot of the ladder).

The Virgin of the Pillar

On the first column of the left-hand nave you can admire the Virgin of the Pillar. This fresco was painted slightly after the middle of the fourteenth century by Stefano da Ferrara.

Ignore the angels above and the two apostles at the side; they were added later. Likewise, the brilliant diadems on the heads of the Virgin and Jesus probably originate from the seventeenth century.

Above the first altar on the left there is the altarpiece of Maximilian Kolbe, also painted by Pietro Annigoni in 1981.

|  |

The Chapel of the Most Holy Sacrament

This is the first chapel of the right-hand nave. The Eucharist is kept here. It used to be called the Gattamelata Chapel, because the family of the leader Erasmo da Narni (nicknamed Gattamelata, 'Honeyed Cat' in 1443) wanted it to be the resting place for his tomb, which you can see on the left-hand wall; on the right-hand wall is his son Giannantonio's tomb (+ 1456).

The Gothic style chapel was completed in 1458. It has a square shape, with four columns in the corners and a cross-vaulted ceiling. The rest has undergone various changes over the centuries. The latest, including the apse behind the altar, took place over the period 1927-1936 and is the work of Lodovico Pogliaghi, a versatile artist and assimilator.

The Chapel of St. James

Following the right-hand nave, you reach the transept which ends in the Chapel of St. James, paid for by Bonifacio Lupi, the Marquis of Soragna (Parma) who held important diplomatic and military responsibilities at the court of the Carraresi family of Padua.

This elegant and spacious Gothic area was completed in the 1370s by one of the most important Venetian sculptors and architects of the day, Andriolo de Santi. The chapel's entrance has five tri-lobed arches.

The chapel's entrance has five tri-lobed arches.

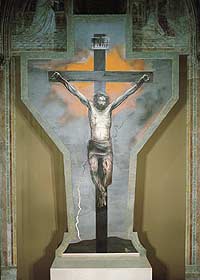

The Crucifixion

The visitor is immediately enveloped by the warm environment inspired by the marble and frescoes, covering every surface of the chapel and whose restoration was finished in 2000. One's gaze immediately gravitates towards the dramatic and majestic Crucifixion, a masterpiece by Altichiero da Zevio (Verona) the greatest Italian painter from the second half of the fourteenth century who finished this work in the 1370s, before the chapel was completed.

The Story of St. James. - The eight windows of the chapel and the partition present a few moments of the life of St. James, taken from the Legenda anctorum o aurea by Jacopo da Varazze (1255?). This was a religious text which was widely disseminated for devotional purposes and concerned itself with traditions and legends which influenced many artists.

The apostle is St James the Great (St. John's brother) whose shrine is Santiago de Compostella (Galizia/Spain), one of the most important destinations of a Christian pilgrimage, especially in the X-XV centuries. The artist is Altichiero da Zevio, with the collaboration of Jacopo Avanzi, from Bologna, whose hand in the fresco is not always identifiable.

Moving towards the ambulatory there is an exit on the right which leads to the Magnolia Courtyard and further ahead, the entrance to the Sacristy; on the left however, there is the Presbytery/choir stalls area. After the Sacristy you come to the first chapel of the ambulatory.

The Chapel of the Benedictions

In this chapel, the faithful like to bless even their personal items, as a long-lasting and visible remembrance of the grace received in the Basilica. The frescoes of Pietro Annigoni also attract our attention, as they were carried out closely following a theme that is very apparent: the tragedy of sin.

Preaching to the fish, on the left (1981): an episode which had the most ancient of origins, Actus beati Francisci et sociorum eius (1327-40), and took place in Rimini in 1223, at the mouth of the Marecchia River.

The Saint, seeing that the heretics and Cathartists were hostile to his preaching, went to speak to the fish, which flocked towards the Saint, darting out of the waves to listen. The artist portrays the Saint resting on a huge boulder (an allusion to Christ) mediator of a faith "represented" by the lively fish rushing to their Creator. Next to him there is a frightened companion of the faith who is hesitantly watching the arriving fish. Aside from the Saint, It is the overall view that is impressive: people and creatures, everyone appears unsettled and about to fall into ruin. This is what happens to a world that rejects God.

The Saint faces the tyrant Ezzelino da Romano (1982). According to the account of the Paduan notary Rolandino (1262) the event narrated in the fresco occurred just before the Saint retired to the hermitage of Camposampiero, therefore in May 1231. Implored by the friends of Rizzardo di San Bonifacio (Verona) imprisoned with others from the Ghibelline sect, St. Anthony turns to Ezzelino III da Romano, to obtain their release. The outcome of the visit is negative. The artist portrays the final phase of the meeting: a refusal with no second thoughts.

The tyrant's obstinance is portrayed through the determined gesture of the hands. Behind him, the grim advisor, pictured in his true identity: the devil, the deceiver.

But Ezzelino is not very relaxed: he reaches out towards the Saint with a frown on his face trying to diffidently scrutinise the source of such simplicity and courage. Anthony has the Gospel in his hand, but it is closed for the tyrant.

St. Anthony, resigned, feels compassion for the tyrant who is a prisoner of himself. Behind, there are the shadows of the prisoners, pushed on by the guards, each indistinguishable from the other.

The Crucifixion (1983). - The proportions, the detachment, the emphasis conveyed by the false wall on which the Crucifix is portrayed elicits an immediate and strong reaction. The eye anxiously follows the curved and bloody legs of Christ. The chest strains downwards and the abdomen is swollen as often happened to those who met their death in this way. The arms are brutally strained and the body appears about to collapse. The face is tortured. The oppressive surrounding atmosphere is furrowed by lightening: the only sign of the echo in nature of this dramatic event. Above, in the centre, a scarlet light, of love and blood, exalts and reveals the meaning of the suffering of Christ, who seems to whisper: "My God, my God, why have You abandoned me?".

Exiting the chapel, let us look up, to the high, serene vaults of the apse of the Basilica and soothe our souls. If we follow the ambulatory, we pass on our right the American Chapel or the Chapel of St. Rose of Lima (1586-1617) the Patron Saint of America, the Philippines and the West Indies; and the Germanic Chapel or Chapel of St. Boniface (673-755), the great evangelist of Germany; and finally the Chapel of St. Stephen, the first Christian martyr, containing clear and skilled frescoes by the Italian Ludovico Seitz (1907), a productive painter who belonged to the "Nazarenes" movement.

If we continue, remaining on the right-hand side, we reach the centre of the ambulatory leading to the Treasury Chapel (Chapel of the Relics).

The Treasury Chapel

This chapel, built in 1691, a Baroque work by Parodi, one of Bernini's pupils occupies a distinct space in the Basilica, without ruining its Gothic coherence.

The architecture transforms into triumph before our very eyes, beginning with the balustrade and six marble statues (also by Parodi).

Behind the balustrade, there is the walkway that allows visitors to admire the "treasure" of the Basilica, hence the name of the Chapel. The reliquaries are collected in three distinct niches and accompanied below by pairs of angels

The entire scene is crowned by celebrating angels (in stucco work by Pietro Roncaioli da Lugano) which lead up to the glory of St. Anthony (in marble, by Parodi). There are further decorations in the drum of the cupola (by Roncaioli) and in the canopy (from the beginning of the last century).

Records of the Saint (in front of the balustrade). Before climbing up to the niches, we can look at objects connected with the Saint, which have been set in this area and on the walls facing the balustrade.

In January 1981, on the occasion of the 750th anniversary of the death of Saint Anthony, and with the intention of specifying the exact state of St. Anthony's mortal remains, St. Anthony's tomb was opened for the second time in history for the "religious pontifical commission" and a "scientific/technical commission". Inside was found:

a large pinewood box, wrapped in four linen sheets and, over these, two highly decorated and embroidered drapes;

inside the large box, a second smaller box (of pine) with two different-sized compartments and a cord with three seals running along the length of the lid; inside three bundles wrapped in crimson red silk and finely embroidered (probably belonging to a cope) and with a precious appliquй trim and each labelled with a parchment indicating the contents which were:

- the entire skeleton, apart from the jaw, left forearm and other minor parts;

- other remains, mostly reduced to dust;

- the tunic, made from ash-coloured wool.

- outside the large box and within the altar which housed it there was:

- a plaque with the date of the Saint’s death, his canonisation and of the transfer of his mortal remains from the little church of Santa Maria Mater Domini to the new Basilica (8 April 1263)

- Lots of little rings (10 white and 50 black) from a necklace or rosary.

To understand all this, we need to think back to the year 1263. The second phase of construction of the Basilica was completed, and on the occasion of the “general chapter” which gathered Franciscans together in Padua with the general secretary of the Order of St. Bonaventure, the tomb of the Saint was transferred from the little church of Santa Maria Mater Domini to the centre of the Basilica, under the present cone-shaped cupola (in front of the Presbytery).

On that occasion the coffin containing the Saint’s remains was opened for the first time, above all to remove some relics to offer for the devotion of the faithful in other churches.

It was a great surprise to see his tongue incorrupt. It was then that St. Bonaventure, with his heart full of admiration, prayed aloud:

O blessed tongue, you have always praised the Lord and led others to praise him! Now we can clearly see how great indeed have been your merits before God.

It was then decided to separately conserve the Saint’s tongue, jaw, left forearm and a few other minor relics. The rest was wrapped up in the crimson red bundles mentioned above, and placed in a smaller box which, in turn was placed in a larger box.

The recent recognition of 1981 provided the opportunity to make an examination of the historical, technical, artistic, anthropological and medical character of all the material discovered. The Saint’s skeleton was accordingly reconstructed and placed on a small cushion in a crystal case, within which were placed two glass caskets containing the other remains. The crystal case was then locked away in an oak casket and placed back into the tomb.

In the Treasury Chapel there is: the Saint’s tunic, the two wooden boxes, the cord and two seals, the three crimson red cloths reconstructed as a cope, the two large decorated drapes, the plaque, some small coins and the rings. All of which can be devoutly observed.

Up the left flight of steps there are three niches which contain relics of St. Anthony and other Saints, and above, gifts donated in recognition or as signs of devotion by wealthy pilgrims who have visited the Patron Saint of Padua. We must instead focus on the most prestigious relics of St. Anthony which are in the central niche. The Saint’s tongue (in the centre). Do not expect it to be a tongue which is bright red in colour. It is still however an inexplicable fact, given that it is a very fragile part of the body that is usually among the first parts to disintegrate after death. More than 770 years have passed since St. Anthony died and this tongue is a perennial miracle, unique in history and full of religious significance, a seal marking the work of re-evangelisation of society carried out by the Saint.

A gilded silver masterpiece, a work by Giuliano da Firenze (1434-36) proudly contains the relic of the jaw (above). More precisely, the lower jaw, contained in a case shaped like a bust, with a halo and crystal glass where the face should be. It was commissioned in 1349 by Cardinal Guy de Boulogne-sur-Mer, who experienced one of the Saint’s miracles: He brought it to Padua the following year, to solemnly organise the placing of the jaw into this reliquary. The cartilage of the larynx (below). This is still incorrupt. These are the parts of the body used in phonation, that is to say, in speech, and thus attracted attention straightaway, although not considered inexplicable like the tongue during the recent recognition in 1981. It was still decided to place it with the Saint’s tongue. The reliquary is the work of Carlo Balljana from Treviso.

Exiting the Chapel of Treasure, on the right there are the following chapels: the Polish Chapel or Chapel of St. Stanislaus (+ 1079), priest and martyr and patron Saint of Poland, then the Austro-Hungarian Chapel or Chapel of St. Leopold (1075-1136), margrave and Patron Saint of Austria; then the Chapel of St. Francis; and finally the Chapel of St. Joseph.

The chapel of the black Madonna

Further ahead, on the right-hand side, there is the Chapel of the Black Virgin.

Here we find ourselves in what remains of the early church of St. Maria Mater Domini (end of XII-beginning XIII) contained within Basilica. St. Anthony certainly prayed here and his dying wish was that he be buried here. His remains stayed here until 1263.

The statue of the Black Madonna which dominated the altar was completed in 1396 by Rainaldino di Puy-l'Evйque, a Gascon artist. Paduans have called it the “Black Madonna” because of her dark complexion, the name also expresses their loving relationship with her.

At the side of the chapel there is the Chapel of Blessed Luca Belludi, dedicated also to St. Philip and St. James the Younger, apostles of St. Anthony. It was added to the Basilica at the end of the fourteenth century, and named after Blessed Luke, St. Anthony’s companion and successor, because his tomb is in the altar. Paduan students often come here, placing their trust in the blessed one’s intercession for the difficult task of preparing for their exams.

The chapel was from almost the beginning however dedicated also to St. Philip and St. James The frescoes by the Florentine Giusto de' Menabuoi are very interesting, and originate from the second half of the fourteenth century (1382). Ruined by the humidity, they have recently been restored and brought back to their former splendour, allowing us to appreciate their considerable artistic level.

The raised sarcophagus is empty these days. This altar/tomb dates from the thirteenth century and tradition has it that from 1263 to 1310 it was the tomb of St. Anthony, when it was located in the Presbytery of the Basilica, under the conical cupola.

The chapel of the tomb of Saint Anthony

The Saint’s tomb has been called the “Ark” from the very beginning. The Saint’s tomb is in the altar in this chapel, at head height. Originally it was located (from 1231 to 1263) in the little chapel of St. Maria Mater Domini (today the Chapel of the Black Madonna) and from 1263 to 1310 in the centre of the Basilica, in the Presbytery, under the present conical cupola. The location of the tomb from 1310 to 1350 is uncertain, however, it might have been in its current position. It has remained in this chapel from 1350.

Until the beginning of the sixteenth century, the style which has decorated the chapel has always been Gothic, with frescoes by Stefano da Ferrara, the same artist who painted the Virgin of the Pillar.

The current decoration was completed in the sixteenth century and is quite harmonious from an architectural and sculptural point of view. It has been attributed to Tullio Lombardo.

The altar is rather invasive, but the artist Tiziano Aspetti (who created it at the end of the sixteenth century) was conditioned by the height of the preceding altar which was difficult to modify. The statues on the altar (St. Anthony between St. Bonaventure and St. Louis of Anjou) are by the same artist, while other bronze workers made the angels, the small gate and the two small branched candlesticks.

The taller ones supported by marble angels are sixteenth century creations by Filippo Parodi.

High reliefs on the walls behind the tomb. - with a bit respect and good manners, it is possible to combine, for whoever may be interested, a pause for prayer and reflection at the Saint’s tomb with brief glance at the nine high reliefs found in the chapel.

- St. Anthony receiving the Franciscan habit. A work by Antonio Minello (1517).

- The jealous husband, whose wife, beaten out of jealousy, is healed by the Saint. The work, begun by Giovanni Rubino (known as il Dentone), was completed by Silvio Cosini (1536).

- The young man resurrected by the Saint. The Saint, miraculously transported to Portugal, resurrects a young man so that he can reveal his assassin in order to exonerate Anthony’s father, in whose garden the young man’s body was hidden. Begun by Danese Cattaneo, it was completed by Girolamo Campagna (1573).

- The resurrected young girl. A young girl, having drowned is resuscitated by the Saint, who does not appear in this representation, even if you can see his Basilica above. The work is by Jacopo Sansovino (1563). It is a well-balanced and powerful representation.

- The resuscitated child. The child is Anthony’s nephew. This is a work by Antonio Minello, with retouches by Sansovino (1536).

- The heart of the deceased usurer is not found where it should be, but in his coffer, as the Saint had declared. This is by Tullio Lombardo (1525).

- St. Anthony reattaches the foot of a young man, who out of desperation had cut it off after kicking his mother. The work of Tullio Lombardo (1504).

- The glass which remains intact, having been thrown to the ground as a challenge by someone who did not believe in the preaching or wonders worked by St. Anthony. Begun by Giovanni Maria Mosca, it was completed by Paolo Stella (1529).

- St. Anthony makes a newborn baby speak, to attest to the honesty of his mother, unjustly suspected by her jealous husband. The work of Antonio Lombardo (1505), Tullio’s brother.

The choir-presbytery complex

To visit this part of the Basilica you need to speak to one of the guards.

The decoration of the apse of the Basilica. The pictorial decoration which covers the apse of the Basilica was created by the Bolognese artist Achille Casanova and his assistants in 1903 and in 1939, and follows a great iconografical project which is not necessary to explain here. The work has been highly criticised, because it was too scholastic and interferes with the pure architectural lines, which it should have simply and discreetly followed. But it is limiting to focus on this one aspect only. This work, in fact, has a certain grandiosity and is certainly unique. It inspires awe when the Basilica is illuminated.

Below, the choir: this is the term for the area behind the main altar or the stalls in which the religious sit to celebrate the “Liturgy of the hours”, which is the public prayer of the Church, when the friars pray for those who have asked for prayers. Until 1649 the choir was in front of the present altar, in the presbytery. This was its position in the majority of churches which had a choir until the Council of Trent, and can still be seen in that position in Anglican churches; the choir was then gradually moved behind the altar so that the faithful could see the altar better and follow the liturgy more closely. The actual stalls of the Basilica’s choir date back to the latter part of the eighteenth century. The previous stalls, a Gothic masterpiece by brothers Lorenzo and Cristoforo Canozzi and their workshop (1462-69), were destroyed by fire in 1749

Pashcal candelabra: masterpiece by Andrea Briosco. On the North of the altar there is a superb paschal candelabra cast in bronze by Andrea Briosco, known as “il Riccio”, which was completed in 1515. It is one of the greatest candle-holders in the in the Western Christian Empire, not only because of its dimensions (3.92m high plus the 1.44m marble base), but owing to its complexity and high level of workmanship.

The Donatello grouping: a marvellous synthesis of life and faith. - Let us conclude the visit to the Basilica, taking a look at some of the thirty works by the great Florentine sculptor Donatello. These were created in Padua, from 1444 to 1450, and represent one of the most fundamental events of the Renaissance and of all Art History, not just in Italy.

The Deposition. - This work (found behind the main altar) made in stone from Nanto (Colli Berici, Vicenza). Four disciples wracked with pain, laying the naked, motionless body of Christ into the tomb. Behind them, the torment of the women is portrayed. Mary Magdalene is in the middle: more than any of the other 43 women, she expresses the horror of being left alone to think about her sin. According to Christian revelation, sin is the reason for death.

The miracle of the mule (above left, behind the altar). The artist sets this famous episode in the magnificence of a Basilica, in front of an altar. Not only scholars marvel constantly at the magic of Donatello who was able to give an unexpected sensation of depth and volume to shallow spaces, using lines, decorations and different coloured materials. One’s gaze descends the lateral vaults, travels across the transversal lines, and like a wave takes in the two groups of men and pushes them towards the altar. Here, light penetrates creating a feeling of the serene peace of presence of the Lord: it is revealed partly by the sanctity and faith of Anthony on one side and partly by the silent voice of nature. The discovery of the presence of God is reflected in the individual expressions of those present: an agitated and anxious humanity before God, a splintering of reactions...

Donatello, like all great geniuses, transcends the culture of his time and appears contemporary. As you can see, the very low relief reduces the volume of bodies, which are flattened and expanded with a painting-like quality. This technique, of which Donatello is a master, is named after the Tuscan terminology “stiacciato”, which means “squashed”.

On the right of the opposite side of the altar, the artist portrays St. Anthony who makes a newborn baby speak (to attest to the honesty of his mother unjustly suspected by her jealous husband). On the bottom right: the ox (winged and with a halo, a symbol of Saint Luke, the evangelist); on the right: a lion (a symbol of St. Mark).

The Main Altar was completed in 1895 by Camillo Boito (brother of the musician Arrigo) and is the last of the various altars built in the Basilica over the centuries. These variations are due to changing sensibilities and liturgical procedures. All of Donatello’s masterpieces, which were once spread about the Basilica, are gathered together here. Here they are described one by one.

Fourteen little angels and the sorrow of Christ. Below, along the front and side panels there are 10 very original angels playing instruments (on ten panels) and 4 singing angels (on two panels, at the side of the Dead Christ). Although these are quite clumsy, like in other artistic representations of children at the time, these putto sculptures kindle an immediate fondness for their childish commitment to their musical activities.

In the centre is the Sorrow of the Dead Christ : a tender portrayal.

The little Tabernacle door depicts Christ dead in his tomb (dated 1496: sculptor unknown). At the sides: on the left, St. Anthony reattaches the foot of a young man, (who, out of desperation, had cut it off after kicking his mother); on the right, The usurer’s heart (which was not found in his chest by the surgeon but in his coffers).

St. Giustina and St. Daniel. - Higher up, above the altar, on the left: St. Giustina (a young Paduan martyr, her cult began in the V century; the great Basilica in nearby Prato della Valle is dedicated to her); on the right, St. Daniel (a young Paduan deacon, martyred at the beginning of the IV century and whose remains are in the Cathedral of Padua).

The altar extends and has two lower wings on which is an angel (symbol of St. Matthew) on the left below, and, St. Louis above; on the right: below, an eagle (symbol of St. John the evangelist) and above, St. Prosdocimo.

St. Louis d'Anjou and St. Prosdocimo. St. Louis (127-497), son of Charles d'Anjou II, King of Naples: he refused the crown and before accepting to be the bishop of Toulouse, he wanted to experience being a Franciscan. His decision had a huge impact on others. He died at 23 years old.

St. Prosdocimo (latter half of III century) founder and first bishop of the city of Padua. His old age has been confirmed by the recent recognition of his bones that rest in the Basilica of St. Giustina.

St. Francis and St. Anthony. - At the Virgin Mary’s side, Donatello portrayed St. Francis and St. Anthony, major players in the religious and cultural life of the thirteenth century.

The Virgin and Child. This is the central theme of Donatello’s symphony. Mary is very young, and though unfinished in some parts, the statue has the fresh quality of a new creation. We can note great beauty united with ever-present painful thoughts. It brings to mind ancient statues, but it is also animated by the motion of life and history.

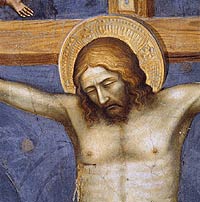

The Crucifix - Behind the statue of the Virgin, the crucifix rises up and dominates the space. As the proportions reveal, Donatello didn’t create this for the altar, but instead meant it to be placed in the middle of the church.

It is seen from below. The nail swells and puckers the veins which cross the right foot. The eye slowly follows in pain the legs that are curved and bent to the right, but are not yet stiff. The abdomen and chest are striking, especially if struck by the light, since they allow the underlying skeleton to be seen. Veins and the tendons that still pulse with life run down the arms. The face is that of a hero which mixes beauty and courage.

Sacristy

The sacristy is preceded by an atrium full of valuable frescoes. They are attributed to a follower of Girolamo Tessari (known as Dal Santo). They portray two miracles: St. Anthony praying to the fish and the glass thrown to the ground which remains intact (both 1528).

In the lunette above the door, there is a beautiful fresco from the second half of the thirteenth century: the Virgin and Child between St. Francis and St. Anthony.

In the bright sacristy, we can admire the frescoes by Pietro Liberi which celebrate, with inspired and unbridled imagination, the glory of St. Anthony (1665).

On the right, above the entrance, the wall is covered by a large wall cabinet, a work by Bartolomeo Bellano (1469-1472). The ten marquetry panels which cover it are by Lorenzo Canozzi (1474-1477); they represent (from the left): Saints Bernardino and Jerome, Francis and Anthony, Louis d'Anjou and Bonaventure; on the panels below the Saints, a still life of books and liturgical objects. On the other wall, there is an oil painting on canvas by Francesco Suman (1847).

Beyond the little room, there is the airy chapter hall (the official meetings of friars are called chapters) originally decorated with a fresco cycle attributed to Giotto. Unfortunately, few fragments remain.

Courtyards

The Noviciate Courtyard

Only groups who are accompanied by the Basilica's religious or authorised personnel may visit this Courtyard.

Exiting the Basilica from the only Sacristy door which opens to the outside, you enter the Noviciate Courtyard, the name of which comes from the fact that the novices' rooms are located along one side. These young candidates for religious life spend a very intense spiritual year in the Community of the Basilica, animating both community life and liturgical celebrations with their presence.

The Noviciate Courtyard, created in the latter half of the fifteenth century in a Gothic style, is amply proportioned; the airiness of the arches, which counterpoints the green of the lawn, and the peaceful atmosphere inspire unforgettable feelings. Added to this a view of the Basilica from the south-east corner that never fails to charm every visitor.

The Magnolia Courtyard (or Chapter Courtyard)

From the Basilica's south door (or from the Noviciate Courtyard) you can reach the Magnolia Courtyard, so-called because of the "Magnolia grandiflora" which was planted in the centre in 1810. The actual courtyard originates from 1433. Here, as in the other courtyards, there are tombs, monuments, plaques and epigraphs, too much to describe in detail here.

The entrance to the Souvenir Shop is on the south side. It contains religious objects and books. Inside the shop, a glass door opens onto the Offices of the Messenger of St. Anthony and the Pilgrim Reception Area for relations with members of St. Anthony's family. The Information Office, open from April to November, is located on the west side of the courtyard, just before the courtyard exit.

The General's Courtyard

Exiting the shop or the Magnolia Courtyard you can enter the General's Courtyard (built in 1435, in the Gothic style, work of Cristoforo da Bolzano). It has this name because the accommodations reserved for the General of the Order (as well as other religious authorities), during visits to the Basilica and its religious community, open onto this courtyard. From this courtyard you can enter the prestigious Anthonian library.

To the west of the Courtyard, you can visit the Anthonian Exhibition, an interesting audio-visual presentation of the life of St. Anthony and the continuation of his work today. A stop here compliments the visit to the Basilica..

Blessed Luca Belludi's Courtyard (or the Museum Courtyard)

You can get here either through the Anthonian Exhibition or the Magnolia Courtyard. This is a majestic Gothic courtyard dating back to the latter half of the fifteenth century. The adjacent rooms are the seats of various organisations: the Institute of Religious Science, the Centre for Anthonian Studies, the Anthonian Museum, containing various works of art of considerable value and the Anthonian Museum of Popular Devotion.

The latter is open to the public, during the summer, and is worth a visit (descriptive brochures are available). It is divided into sections with each area referring to different aspects of the world of devotion and pilgrimage to the Saint.

St. Anthony's Square

Two chapels open onto St. Anthony's Square which, while not well known, are true artistic treasures

The Oratory of St. George

This chapel was built by Raimondino Lupi di Soragna (Parma) in the latter half of the fourteenth century as a burial chapel for himself and his family who had retired in Padua. It was completed by his relative Bonifacio Lupi. Just like St. James' Chapel in the Basilica, the oratory was completely frescoed by Altichiero da Zevio and his aides. Art lovers must not miss this splendid occasion. The entrance fee is very modest and there are detailed guides available.

To visit, ask one of the guardians, who can be found in the adjacent building which connects St. George's Oratory to the little church on the right, popularly known as the School of the Saint, the 'Scoletta'.

The School of the Saint

This term originates from Venetian tradition. It refers to the seat of the Arch-confraternity of St. Anthony, which boasts of a centuries long history and which is still an active charitable society. Nationally it is known for the "Goodness Competition" for schools.

In the fifteenth century the Arch-confraternity ordered the construction of the little church on the ground floor and at the beginning of the sixteenth century, the conference room above it. In this room you can admire sculptures, frescoes and paintings of considerable interest; in particular three frescoes and a sinopia drawing by the young Titian (1511) depicting the Saint's miracles.

The Gattamelata monument

In the Basilica, in the Chapel of the Most Holy, there is the Tomb of Erasmo da Narni (nicknamed Gattamelata, 1443) Here we can admire the renowned equestrian monument, a bronze masterpiece by Donatello (1453), which uses, for the first time in modern history, the ancient theme of the equestrian monument. Funereal symbols, engraved onto the cenotaph, ensure that the memory of the unyielding leader remains vivid.