The Natural History Museum

The Natural History Museum first opened its doors to the public on Easter Monday in 1881, but its origins go back more than 250 years.

It all started when physician and collector of natural curiosities, Sir Hans Sloane, left his extensive collection to the nation in 1753.

Originally Sloane’s specimens formed part of the British Museum, but as other collections were added, including specimens collected by botanist Joseph Banks on his 1768-1771 voyage with Captain James Cook aboard HMS Endeavour, the natural history elements started to need their own home.

Sir Richard Owen, Superintendent of the British Museum’s natural history collection, persuaded the Government that a new museum was needed. He had an ambitious plan – to display species in related groups and to exhibit typical specimens with prominent qualities.

The chosen site in South Kensington was previously occupied by the 1862 International Exhibition building, once described as ‘the ugliest building in London’. Ironically, it was the architect of that building, Captain Francis Fowke, who won the design competition for the new Natural History Museum.

However, in 1865 Fowke died suddenly and the contract was awarded instead to a rising young architect from Manchester, Alfred Waterhouse.

Waterhouse altered Fowke’s design from Renaissance to German Romanesque, creating the beautiful Waterhouse Building we know today. By 1883 the mineralology and natural history collections were in their new home. But the collections were not finally declared a museum in their own right until 1963.

Collections

With more than 70 million specimens , ranging from microscopic slides to mammoth skeletons, the Museum is home to the largest and most important natural history collection in the world.

It all started with Sir Hans Sloane, an 18th century collector, whose collection of 80,000 items was brought by the nation. Over the years, voyages of discovery, such as Cook's epic journey aboard the HMS Endeavour, have boosted our collections. Many benefactors have also made contributions.

The scope of our specimens is simply vast. They include material from the ill-fated dodo, meteorites from Mars and a full-size blue whale skeleton . They cover almost all groups of animals, plants, minerals and fossils, and range in size from cells on slides to whole animals preserved in alcohol.

In total, there are:

- 55 million animals, including 28 million insects

- nine million fossils

- six million plant specimens

- more than 500,000 rocks and minerals

- 3,200 meteorites in our collections

We also have the world's finest natural history library , with the largest collection of natural history library materials in the world including books, periodicals, original drawings, paintings and prints, manuscripts and maps.

Waterhouse Building

When you arrive, pause to take in the huge facade and high, spired towers. The rounded arches and grand entrance were inspired by basalt columns at Fingal's Cave in western Scotland. This is one of Britain’s most striking examples of Romanesque architecture.

The huge, imposing Central Hall leads to a grand staircase, which rises to the second floor of galleries. Up above, you’ll see glass and bare iron. This was purposely left exposed by Waterhouse to show the beauty of the building materials.

Remember to look upwards to the plants and animals depicted on the intricately painted ceiling of the Central Hall. The North Hall ceiling alone has 162 individual panels covered with plant paintings.

Terracotta tiles provide decoration inside and outside the building. Many feature relief carvings of plants and animals. The buff and cobalt-blue terracotta is both attractive and practical, as a hardy material that could resist the acid smogs of Victorian London.

In his design, Alfred Waterhouse included elaborate sculptures of plants and animals on the interior and exterior of the building, to represent biological diversity. Those on the western wing are of living forms, while those on the eastern side show extinct creatures.

Ceiling panels

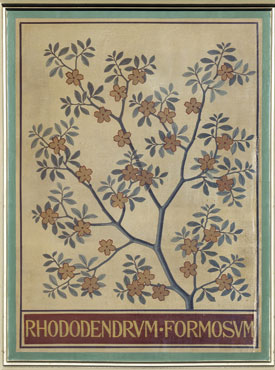

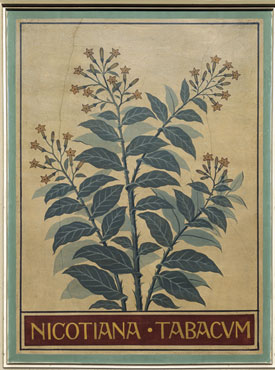

High above visitors to the Natural History Museum is an art exhibition, but one you could easily miss if you didn’t know it was there. Look up from the busy Central Hall in the heart of the Museum and you’ll find a wonderful spread of ceiling panels decorated with plants from every corner of the globe. Beautiful in design, richly coloured and gilded, each has a story to tell.

They speak vividly of an era when specimens of plants from around the world flooded into Britain, sparking an explosion of interest in botany and horticulture, with new glasshouses and public parks springing up all over the country.

Explore the fascinating histories of these exotic species and British flora in this slideshow.

Who painted them? Architect Alfred Waterhouse, who designed the Museum, probably created the original drawings. To translate his ideas into reality, Waterhouse chose the firm Best & Lea. They worked with him on later projects including the magnificent ceilings of Manchester Town Hall.

|

|

Few can imagine a day that doesn’t start with a fragrant cup of coffee. Despite its name, Coffea arabica is native to the mountains of Ethiopia. Plantations were established by the Dutch in the East Indies in the seventeenth century, from where seeds were taken all over the world.

The drug digitalin was first isolated from the foxglove (Digitalis purpurea) in 1875, and went on to revolutionise the treatment of a common and previously incurable heart condition.

|

|

The ornamental plant that would truly change the face of Victorian gardens was the rhododendron. The climate of the Himalayan foothills from which it came was very like that of Britain, and so the plants often did extremely well in British gardens.

First brought back to Europe by the Spanish, tobacco was used medicinally as a cure for gluttony and the respiratory disorder ‘rheums’. Raleigh introduced smoking to the court of Queen Elizabeth - even persuading her to have a puff.

|

|

Chocolate as prepared by the people of the New World was a bitter drink. Collector Sir Hans Sloane wrote from Jamaica that it was ‘nauseous, and hard of digestion, which I suppose came from the great oiliness’. He added milk and sugar to the recipe and so brought the first milk chocolate drink to the UK.

Geological Museum

The Geological Museum – now the Earth Galleries – started life in 1841 as part of the Geological Survey.

After three homes in 100 years it moved to South Kensington, into a building designed by Science Museum architect Sir Richard Allinson and JH Markham.

You can see the words ‘Geological Survey Museum’ carved over the Museum entrance in Exhibition Road.

The building, which shares similarities in appearance with the Science Museum, was built between 1929 and 1933 at a cost of £220,000, and opened its doors in July 1935.

In 1985 it merged with the Natural History Museum, adding a collection of more than 30,000 minerals. In 1988 the Lasting Impressions gallery was opened to connect the two.

The Earth Galleries redevelopment of 1996 to 1998 created the Atrium and six new exhibitions.