Westminster Cathedral - a Brief History

Westminster Cathedral is one of the greatest secrets of London; people heading down Victoria Street on the well-trodden route to more famous sites are astonished to come across a piazza opening up the view to an extraordinary facade of towers, balconies and domes.

The architecture of Westminster Cathedral certainly sets it apart from other London landmarks, owing more to the Byzantine style of the eastern Roman Empire than the familiar Gothic of our native cathedrals.

A Roman Catholic Cathedral like no other

The Architect's Journal described Westminster Cathedral as a 'great religious building which, though clearly rooted in the architectural concerns of the late nineteenth century, has timeless qualities which set it apart from more commonplace works of the age.'

Itself a supreme achievement of art, the Cathedral is home to many distinguished works of artistic merit. True to the vision of its founder, Cardinal Vaughan, successive generations have embellished the great building with decoration of the highest quality. This great house of God reflects the highest aspirations of humanity, and raises the mind toward the glories of heaven.

The following pages provide further background about the Cathedral, including a comprehensive tour of the building.

A Brief History

The Cathedral site was originally known as Bulinga Fen and formed part of the marsh around Westminster. It was reclaimed by the Benedictine monks who were the builders and owners of Westminster Abbey, and subsequently used as a market and fairground. After the reformation the land was used in turn as a maze, a pleasure garden and as a ring for bull-baiting but it remained largely waste ground.

In the 17th century a part of the land was sold by the Abbey for the construction of a prison which was demolished and replaced by an enlarged prison complex in 1834. The site was acquired by the Catholic Church in 1884.

The Cathedral Church of Westminster, which is dedicated to the Most Precious Blood of Our Lord Jesus Christ, was designed in the Early Christian Byzantine style by the Victorian architect John Francis Bentley. The foundation stone was laid in 1895 and the fabric of the building was completed eight years later.

The awesome interior of the Cathedral, although incomplete, contains fine marble-work and mosaics. The fourteen Stations of the Cross, by the sculptor Eric Gill, are world renowned.

Before the Cathedral

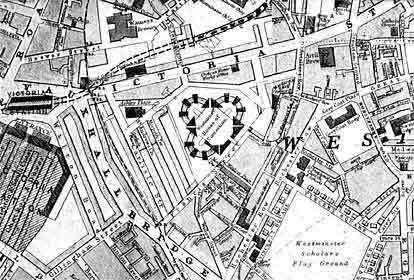

"That land is for sale, I wish you to buy it." Cardinal Manning was addressing his solicitor, Alfred Blount, in November 1882. What both men were looking at, from the Cardinal’s residence at the bottom of Carlisle Place, was Tothill Fields Prison. Blount formed a company and bought the site in 1884. The western half was immediately sold to the Cardinal at cost, the remainder to a property developer. On the land sold to the Cardinal now stands Westminster Cathedral. Tothill Fields Prison was formally entitled the Middlesex (Westminster) House of Correction.

Established by Act of Parliament in 1826, it opened in 1834. It was built on an eight acre site of open ground, now enclosed by Morpeth Terrace to the west, Francis Street to the south and east, and Ashley Place and Howick Place to the north.

From 1618 a much smaller prison, Tothill Fields Bridewell, had stood immediately north of Greencoat School (now a pub) and west of Artillery Row. It was knocked down in 1836, two years after the new prison opened, and the site is now occupied by shops and the Army and Navy stores.

The Tothill Fields Prison of 1834 was built in the form of a shamrock or ace of clubs, each ‘leaf’ effectively forming a separate prison, with a planted courtyard in the centre and exercise yards beside each brick-built cell block. The main entrance, of massive granite blocks with iron gates, opened onto Francis Street. North of the planted courtyard was the prison governor’s house surmounted by a chapel. ‘Vast, airy, light and inexorably safe’, only one inmate escaped from the prison, when the door-keeper absentmindedly laid down his key.

Initially for both men and women with sentences less severe than transportation, from 1850 it was restricted to convicted female prisoners and males below 17 years. Each of the three prison ‘leaves’ contained about 300 prisoners, the one on the left for the boys and the other two for women.

Westminster Cathedral, Clergy House and the Choir School now stand on the site of the boys wing and a part of one of those occupied by the women. The rest of the prison complex now lies beneath Ambrosden Avenue, Ashley Gardens and Thirleby Road.

We know much about the prison from Henry Mayhew’s ‘Criminal Prisons of London’ written after a visit there in 1861. It operated on the ‘silent associated’ system in which inmates mixed but were not allowed to talk among themselves. Of course they did and it is significant that by far the main punishment was restriction of diet (usually for talking).

The most serious punishment, whipping, had only been inflicted twice in the five years 1851-55, considerably less than elsewhere. Mayhew wrote that the staff of the boys prison were entitled to the highest praise, enforcing strict discipline with a minimum of physical coercion.

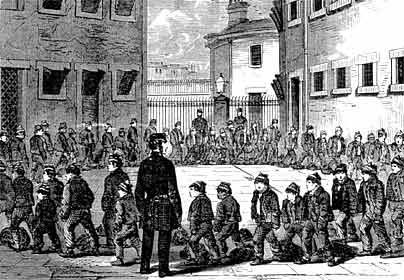

The oldest boy in 1861 was eighteen, having lied about his age to get in. A number were aged six and one as young as five, having stolen 5/9d from a till (his second offence). But the great majority were 14-16 year olds. Almost all had no trade or occupation and most could not read or write. On arrival the boys were given a bath and a meal and issued with the prison uniform of a tricolour striped woollen cap with earflaps (used also as a night-cap in the unheated cells), an iron grey (prison blue for minor offenders) three-piece suit without pockets, check shirt, stock, boots and a small red cotton handkerchief to be tied to a buttonhole.

The boys were identified by numbers on the left arm. A yellow number one identified the 1st class - sentenced to more than three months, a two denoted a sentence of between fourteen days and three months (2nd class), while 3rd class inmates (fourteen days or less) bore no number. A badge was worn for a sentence of two years or more, a yellow ring around the arm denoted penal servitude and a yellow waistcoat collar committal for larceny or felony. Also worn, often proudly, was a red number revealing how many times they had been imprisoned before - one fourteen year-old as many as seventeen.

The boys were awakened by a gun fired at 6.25am. Then followed a communal wash in cold water, Chapel and breakfast of oatmeal gruel (porridge), bread and water, the basic diet at all three meals. Most then worked at oakum picking (unravelling rope for use in caulking the seams of vessels). Other work consisted of mending clothes and shoes, carpentry and gardening. An hour was spent in exercise and another in the school-room. At midday dinner the 2nd class prisoners received tinned cold meat (beef or mutton) with potatoes twice a week and oxhead, barley and vegetable soup twice a week, while the 1st class received this superior diet (and cocoa at breakfast) six days out of the seven. Lock-up was at 6pm.

Most were in for theft, over a third for picking pockets. As one boy put it "I seem to like thieving". But others were there for knocking at doors and running away, an eight year-old had been sentenced to fourteen days and a flogging for taking some half-dozen plums from an orchard, and boys aged ten and eleven were here for spinning a top!

Nearly half were recommittals (against 25% nationally). One youth was suspected of throwing stones at a street lamp just to get a month’s shelter. Many were fending for themselves on the streets of London. They looked on the prison as a place where they would at least be given shelter, food and warm clothing. Indeed Mayhew was prevented from using a drawing of the boys at breakfast as it would have made the place seem far too comfortable!

Mayhew described the part of the prison occupied by the women in less detail. They wore close white caps with deep frills and loose blue and white spotted dresses. They carried the same identifying numbers as the boys and, like them, longer term prisoners received the better diet. Over half were recommittals, many for non-payment of fines. One girl of eight had been sentenced to three months for stealing a pair of boots. When asked why she replied "I hadn’t got none of my own". Besides oakum picking, there was straw plaiting, knitting and laundry work. There were two school-rooms, one of them for girls of up to sixteen, and a nursery where those with young children could look after them when not working.

So why did Tothill Fields Prison, well-built and well-run, close after less than fifty years. Two reasons, I think. Firstly it was not an effective deterrent. Recommittals were twice the number elsewhere and some seemed happy to return. The regime was strict rather than harsh and those released often went out into a harsher and less secure world. The prison was enlightened and enlightenment can be expensive. The cost per prisoner at Tothill was a third more than at Coldbath Fields House of Correction, Clerkenwell. But if the prison had not been built where and when it was, or if, perhaps, its regime had been harsher and more cost effective, Westminster Cathedral would not stand where it does today.